Internships and undergrad research

These are some brief notes on stuff I did over the summers and in UROPs as an undergrad.

SuperUROP - Bayesian theory of mind

I was undergrad researcher in Josh Tenenbaum's lab. I worked on theory of mind AI - algorithms that infer a person's goals and beliefs based on the person's actions.

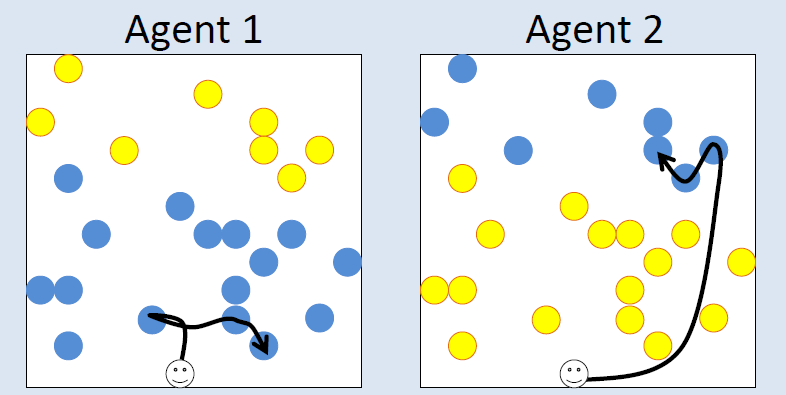

Here's an exact replica of a simple problem that my code can now solve. You see two agents (Agent 1 and Agent 2) walking around and picking up blue and yellow balls. Their paths are shown below. Using your intuition, which agent prefers blue balls more?

Most people would say that Agent 2 likes blue balls more than Agent 1 does. This is a theory of mind task - you are trying to reason about the agents' goals, based on their actions. I use an "inverse planning" algorithm to solve theory of mind problems. Essentially, the observer considers many different possible hypotheses for what the agent could want. For each hypothesis, the observer simulates what the agent would do, and compares this to the observed actions. The simulations that match the observed actions, correspond to likely hypotheses.

There's some more context, as well as computational results for the problem above, in this poster, but this project is still a work-in-progress at this point.

edX summer 2013 - crowdsourced hinting

My summer work, explained using only the ten hundred most used words. (Like in this funny picture .)

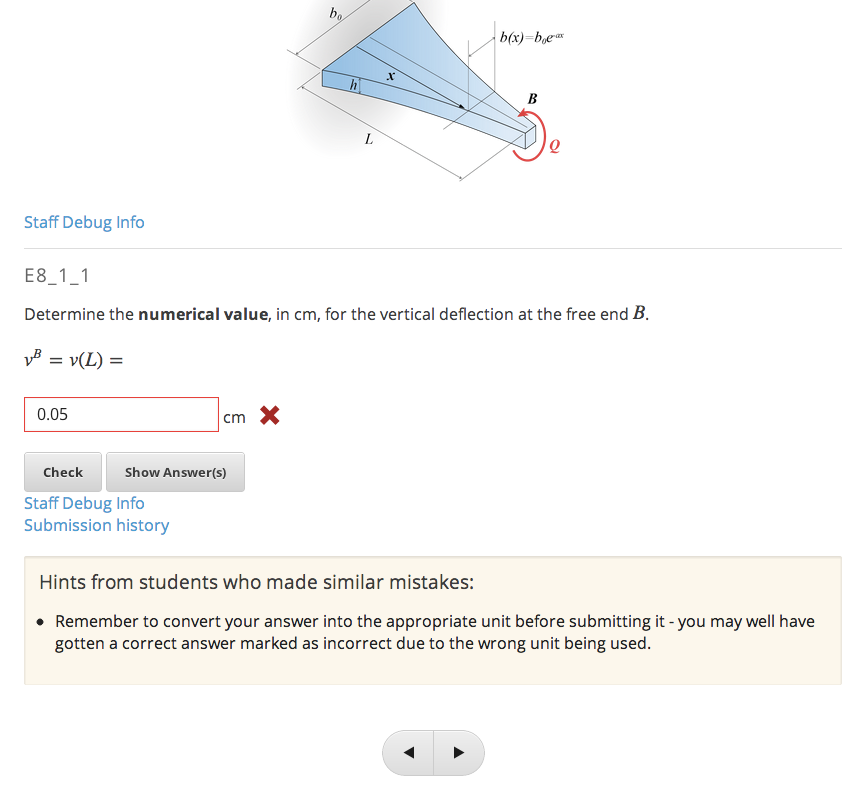

When large classes move on line, some things that teachers usually do to help students are no longer possible. There are so many students in a class that a student can't ask a teacher for help when he/she is stuck on a problem. Simple number problems can become very annoying for students if they can't find where they went wrong.

We want to make on line learning less annoying by having students help each other on problems. When a student gets a problem wrong, and then later figures it out, he/she is asked to write directions for other students who get the same wrong answer. If other students get this wrong answer, they see the directions that the first student wrote. They then tell us whether the directions were good or not, letting us show only the best directions to students over time.

There are many questions we have about this idea. Like: Will students try to write good directions, even if they don't get points for doing so? Can students write directions that don't give away the answer to the problem?

This summer, we tried our directions idea on a problem in a real class. Out of the students who answered our problem right, almost a third of them wrote directions for us, and almost all of the directions we got were good. None of them gave away the answer. This suggests that students are willing to help other students, even without points.

A version of this description will appear on the edX blog soon, hopefully.