DeepHear - Composing and harmonizing music with neural networks

Introduction and tl;dr

I trained a network to generate random bars of music, based on Scott Joplin's ragtime music. It is a fully connected Deep Belief Network, set up to perform an auto-encoding task. The results sound something like this ![]() . (Warning: sound, obviously. Each snippet lasts around 17 seconds.) Or this

. (Warning: sound, obviously. Each snippet lasts around 17 seconds.) Or this ![]() .

.

If the music doesn't work, try reloading the page first - the Javascript library I use to play MIDI files can be unreliable at times.

Even better, we can use prior-sampling techniques to harmonize a melody. We give the neural net an incomplete output, and we tell the neural net to modify its internal node activations until its output meshes well with the incomplete sample we gave it. The incomplete sample is the melody, and the complete output is the harmony.

For example, if we give our net this melody![]() ...

...

It comes up with this harmony![]() .

.

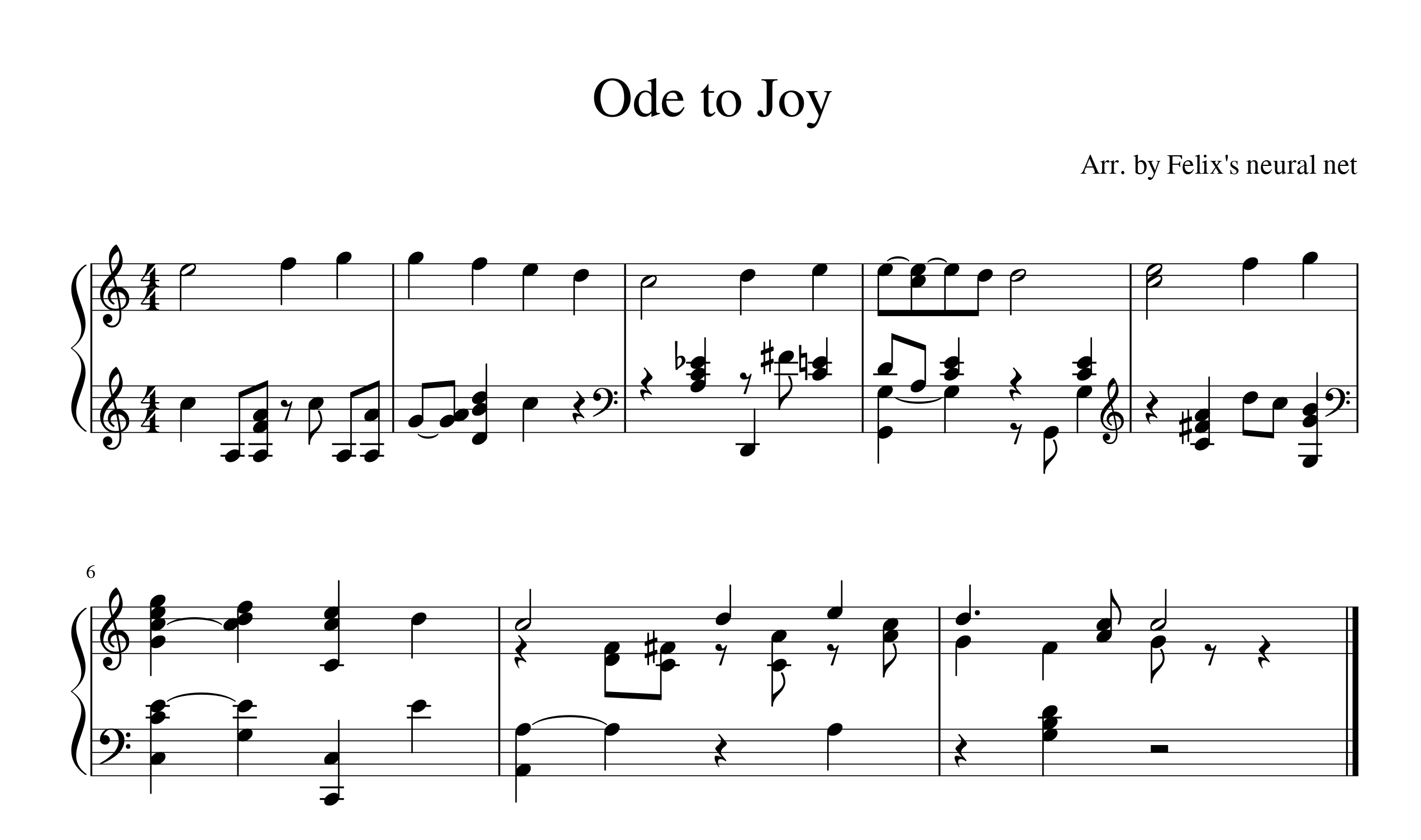

As you can tell, it's not perfect at making beautiful music yet, but it clearly understands basic chords and rhythms as they relate to a melody. Just for fun, you can look at the sheet music representation, as well. (I tried really hard to make this sheet music readable, but the notes are just everywhere. This in fact reveals a weakness of the neural net - it doesn't understand voice continuity very well.)

If you want to see more cool demos, head for the results section below.

Deep Belief Nets

This section tries to explain what a Deep Belief Net is, and how it processes data. If you really don't want to see math, you can skip ahead and look at more cool results. But, hopefully, I can help you understand a little bit of how neural nets work, if you just stick with me.

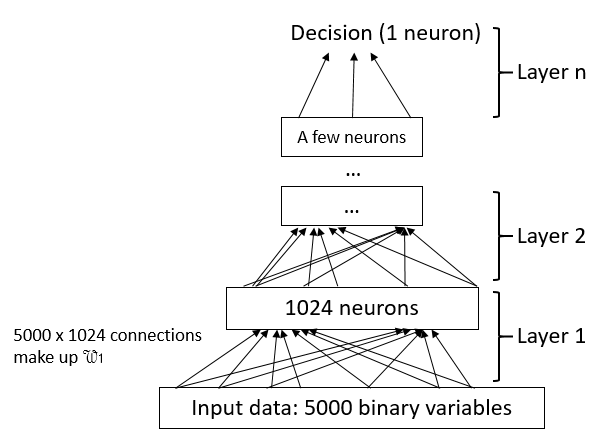

The music on this page is generated with a Deep Belief Net (DBN). A DBN is essentially a pyramid of artifical neurons split into several layers. Each layer takes in data from the layer below it, and outputs to the layer above it. Each layer is also smaller than the layer below it. In theory, this creates a funnel of information processing, where each layer converts a large amount of noisy data into a smaller amount of better-structured information. A DBN is a type of neural net; almost all of the intuition about DBNs in this post carries over to other neural architectures.

A diagram of a typical DBN architecture. Each box represents a layer of neurons. In my diagrams, the input connections to a neuron are part of the neuron, because the input connections are controlled by the neuron's parameters. (The output connections, in contrast, are controlled by the parameters of the neuron in the layer above.)

The neurons in a DBN (or in any other neural network) are just simple mathematical functions. A neuron might have $X_1$ as an input vector and $x_2$ as an output. The elements of $X_1$ are made of some combination of the outputs of the previous layer, or some parts of the input data. In a DBN, $X_1$ consists of all of the outputs of the previous layer (or of the input data, for the first layer), so we call a DBN "fully connected". The relationship between $X_1$ and $x_2$ might be as follows: $$ x_2 = \sigma(W \cdot X_1 + b) $$ where $W$ (a vector of the same size as the input $X_1$) and $b$ (a scalar) are variables internal to the neuron, and $$ \sigma(a) = \frac{1}{1+e^{-a}} $$ is a "non-linearity" that forces $x_2$ to fall between $0$ and $1$.

Essentially, this neuron is adding together some combination of its inputs, and then chopping off the result so it is between $0$ and $1$. All of the results are then combined together and fed into the next layer, which does the same thing, except with a different $W$ and $b$, and so forth.

To make things more concise, you can look at the network an entire layer at a time, instead of one neuron at a time. The input of a layer is $X_1$, which is either the input data, or all of the outputs of the previous layer. The output of a layer is $X_2$, which is now also a vector. A layer actually has the same equation as a neuron, except vectorized: $$ X_2 = \sigma(\mathcal{W} \cdot X_1 + B) $$ Since this layer is now making all of the $X_2$'s in parallel, $\mathcal{W}$ is now a matrix of size $|X_2| \times |X_1|$, and $B$ is now a vector of the same length as $X_2$. You should see that $\mathcal{W}$ is just all of the individual $W$'s of the neurons stacked together, and $B$ is just all of the individual $b$'s of the neurons stacked together. (And $\sigma$ just operates on each element of its input independently.)

So, an entire DBN is like $$ X_{out} = \sigma(\mathcal{W_3} \cdot \sigma(\mathcal{W_2} \cdot \sigma(\mathcal{W_1} \cdot X_{in} + B_1) + B_2) + B_3) $$ That's it. With this equation, you can do some pretty serious image recognition. As a reminder, each layer is usually smaller than the one below it, so that $X_{in}$ might be a vector of length $10000$, while $X_{out}$ may be a single number or a small vector.

Of course, the real trick is finding $\mathcal{W}$'s and $B$'s that actually solve your problem, a process called "training". Training is a hard problem, because this neural net is highly non-linear (so it's almost impossible to tell if you've found the best solution), and there are a lot of unknowns within each $\mathcal{W}$ to find. I don't want to talk too much about training here - if you are curious, you should Google "backpropagation" and "Deep Belief Networks". In very few words, to train a neural network, you start with a guess for each of the parameters. You feed your training data (let's say a binary matrix that corresponds to a piece of music in sheet music form) into your network. You compare the output to what you expect the output to be (let's say a 0 to 1 rating of how beautiful the music is), and calculate an error amount. Then, you calculate the gradient of all the parameters with respect to your error - that is, how much moving each of your parameters a tiny amount will affect your error. This can be done with some basic (though painstaking) calculus. Then, using the gradient, you tweak your parameters slightly so that the error becomes smaller. Then, you repeat the process.

DBNs have an additional piece of trickery: a very good initial guess for $\mathcal{W}$ and $B$. We'll talk a little more about this later.

If your initial guess is good (and initial guessing is a huge challenge in its own right), you should end up converging on a network that accurately gives you the outputs that you expect, when you feed your training inputs. This training process works for many kinds of networks (tall ones, short ones) and many kinds of input data (images, speech, word counts). Therefore, it has become a sort of general-purpose AI tool.

Flipping a DBN - autoencoders

But there's a problem with DBNs - they are designed to take in a lot of data, and spit out a tiny amount of data. What we want is the opposite - given a very simple cue (or no cue at all!), our network should make an entire piece of music, which is a vast amount of data.

You might already see a very simple way to make a DBN that generates a lot of data - simply make an inverted pyramid, with a very small input layer, growing middle layers, and a large output layer. This, actually, is a pretty solid approach. There is only one problem: what do you use as input? You might first try a random vector of 1's and 0's. This would associate a random short "label" with each snippet of music, and have the DBN generate the snippet that goes with each label.

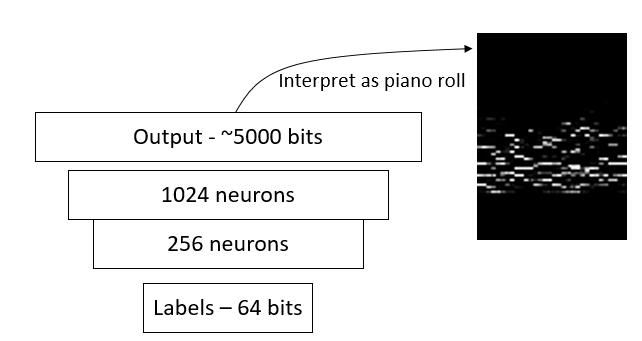

An "inverted" neural net that can generate music from random labels. We train this net by associating a random 64 bit number with each snippet of music we have.

I tried the label-to-snippet idea, with the architecture shown above. It sort of works: here's a sample ![]() . And another.

. And another. ![]() . But, if you listen carefully, you can tell it's not as good as the stuff in the introduction. There are a lot of weird dissonances, and the music often sort of lurches to a stop.

. But, if you listen carefully, you can tell it's not as good as the stuff in the introduction. There are a lot of weird dissonances, and the music often sort of lurches to a stop.

The problem is, the input data (the labels) are too random. They have nothing to do with the actual music snippets I used to train the net. Because the labels are chosen randomly, two very different-sounding pieces can have labels that are off by only one bit, or even worse, the exact same label. And two very similar pieces can have very different labels. One way to fix this problem is by manually labeling each snippet with some categorical information - perhaps the chords used, or the mood, or whatever. But that would be cheating. Ideally, we want a system that learns how to compose good music from just the music itself, not from human guidance.

There's a really cool solution to the labeling problem in the literature: autoencoding DBNs. Autoencoding DBNs train (1) a large-to-small classifier network that labels each snippet of music and (2) a small-to-large generative network that turns a label into a snippet of music, at the same time! (Obviously, you can replace "snippet of music" with the data type of your choice.) This way, you can get labelled music and a trained music generator in one shot.

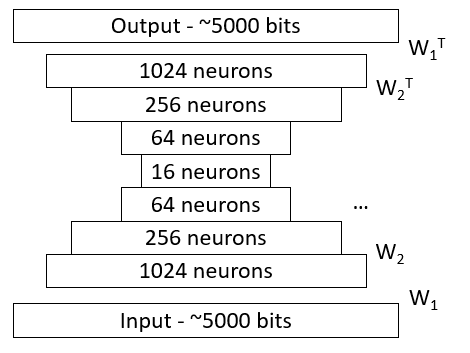

The autoencoding DBN used to generate the music in this post. This net is trained to reconstruct its input at its output, hence the name "autoencoding". The $\mathcal{W}$'s and $\mathcal{W}^T$'s are meant to show the connections between each layer and the next.

An autoencoding network (shown above) relies on a powerful concept in neural networks called "shared weights". Each classifying ("encoding") layer shares the same $\mathcal{W}$ as a corresponding generating ("decoding") layer; the decoding layer simply has a tranposed $\mathcal{W}$. You can think of this $\mathcal{W}$ as a lossy compression code that summarizes a large data vector into a smaller one. The same compression code can later be used to decompress the smaller vector into something that resembles the original larger vector.

So, an autoencoding DBN has several encoding layers, followed by a symmetric set of shared-weight decoding layers. To train it, you simply use the backpropagation algorithm described above, with the error equal to the difference between the input and output. (Ideally, if the autoencoder were perfect, the output would exactly resemble the input, despite the fact that we compressed and decompressed the latter to make the former.)

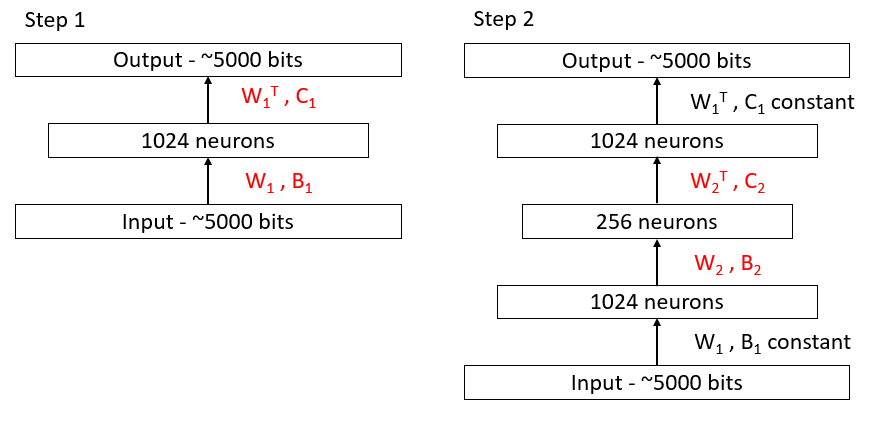

There is a clever way to make an initial guess for the parameters of an autoencoding DBN: you train each encoder and its corresponding decoder in isolation. Convinently, there is a fast algorithm for training a single level encoder/decoder system, using restricted Boltzmann machines (RBMs). If each indvidual layer is set up to be an autoencoder already, then the entire DBN should already be a decent autoencoder. You can then use backpropagation on the entire network to do some fine-tuning. This initial training procedure is summarized in the diagram below.

Pre-training an autoencoder one layer at a time, using restricted Boltzmann machines. At each step, a new pair of layers are added to the network: a compressing layer plus a corresponding decompressing layer. The weights of the new layers are then set to minimize the reconstruction error. The old layers are fixed - in this diagram, only the red variables are changed at each step. This breaks the problem of training an autoencoder net into a bunch of more tractable steps. After all the layers are added, we can run backpropagation on the entire network to fine-tune the parameters.

To generate music, we extract and use the decompressing part of the net, starting at the 16-neuron stage and going upwards. We feed a random input into the 16-neuron stage, and interpret the output as music. Since neural nets output values that are continuous between 0 and 1, we have to threshold the output at 0.5. (You might notice that we use a 16-bit label for each snippet in this net, as opposed to a 64-bit label in the inverted DBN. I had a lot of trouble getting an inverted DBN with 16-bit random labels to converge, probably because of the bad labels problem I discribed earlier.)

Listen to some results

Generate a random sample! ![]()

Your sample id is: (ungenerated) .

The music you are hearing is generated by the autoencoding net I described above. I trained it on about 600 measures of Scott Joplin's ragtime music. The music was converted into a binary matrix, where each column represents a 16-th note worth of time, and each row represents a pitch. Ones and zeros represent the presence and absence of a note at a partcicular time. You can see an example of this matrix in the inverted neural net diagram in the previous section. The music was split into overlapping 4-bar segments, which is why all the samples are 4 bars long.

Training was done using RBM initialization, then gradient descent. Gradient descent was performed on the L2 norm (sum of the squares) of the difference between the input training data and the output of the neural net. The training reconstruction error averaged around 10 wrong notes out of 5000. That is, if I asked the autoencoder to compress, then decompress, a snippet, I would expect the decompressed verson to differ from the original at about 10 places.

Secret: I'm not actually querying my neural net in real time when you push the generate button. (Although this wouldn't be impossible - on my laptop, generating a sample takes about one second.) Instead, I generated 1000 samples in a batch, and saved all the midi files to my webserver. When you click the generate button, I randomly give you one of the 1000 samples.

If you click on the generate button enough times, you might be able to catch my net plagiarizing! For example, sample number 138 ![]() sounds like this. This is in fact the intro to "The Easy Winners", part of the training data. The reason is simple: there are $2^{16} \approx 60000$ possible labels for the input of the generative net, because labels are only 16 bits long. Of those, 600 labels have to correspond to actual pieces of training data, because our autoencoder assigns each piece of training data a (hopefully unique) label. Therefore, around 1% of our random samples will correspond directly to training data. Let me know if you can recognize the tune of any other samples.

sounds like this. This is in fact the intro to "The Easy Winners", part of the training data. The reason is simple: there are $2^{16} \approx 60000$ possible labels for the input of the generative net, because labels are only 16 bits long. Of those, 600 labels have to correspond to actual pieces of training data, because our autoencoder assigns each piece of training data a (hopefully unique) label. Therefore, around 1% of our random samples will correspond directly to training data. Let me know if you can recognize the tune of any other samples.

If this net plagiarizes entire songs every once in a while, how original are its compositions? To answer this question, I searched the entire training set for the snippet that was most similar to each generated piece. I defined similarity as the percentage of notes in the generated piece that are also in the training piece. (This way, taking a training piece and deleting a couple of notes counts as 100% similar.) I found that, on average, each generated snippet copies 59.6% of its notes from some training snippet.

The 60% plagiarism statistic makes it seem like my net is quite derivative. But, you don't need to change a large percentage of the notes in a piece to get something that has a completely different sound. For example, this generated piece ![]() is actually 80% similar to this original piece

is actually 80% similar to this original piece ![]() . Would you say they sound the same in any way? Probably not - they share a chord progression, but the melody is quite different.

. Would you say they sound the same in any way? Probably not - they share a chord progression, but the melody is quite different.

Most of the time, the net copies the majority of its notes from one training piece, then adds variations. This is something like taking the structure of a song, and improvising your own melody on top of it. Sometimes, it comes up with something quite original, and occasionally, it copies the input, due to the constraints of the network topology.

Harmonizing melodies with constrained prior sampling

We want to demonstrate that our neural net actually learned something about the structure of music: harmonies, rhythms, and chord progressions. One way to do this is to use our neural net to solve a new problem that it wasn't trained to do: harmonize a (not ragtime) melody. This shows that our net's connections encode real patterns about music that can be applied to other musical problems.

Harmonization is a completion problem: you are given a part of a piece, the melody; and you have to produce the whole piece, the melody plus the harmony. In the context of autoencoding neural nets, we are given part of the output, and have to solve for the whole output. The space of all valid outputs is defined by the input of the generative net, the bottleneck of 16 neurons that controls the label. Any output that can be produced by some combination of 16 neuron activations is valid; anything else is not. We therefore want to find a label which results in an output that matches as much of the given melody as possible.

If you are familiar with probabilistic models, you might recognize this as an inference problem using conditional probability - given a generative model $P(Y_{out} | X_{in})$, you want to estimate the $X_{in}$'s that maximize $P(X_{in} | Y_{out} = y)$. However, our neural nets do not lend themselves to probabilistic analysis very easily. Therefore, we treat the generative model as a black box, and simply search for labels that result in good snippets.

We can use gradient descent (the same algorithm used to train neural nets) to find labels $L$ that result in snippets $S = gen(L)$ that are good. First, we need to define an error quantity $err(S)$. In our case, $$ err(S) = \sum_{\text{pitches } i, \text{timesteps } t} ((i, t) \text{ in melody}) \cdot (1 - S[i, t])^2$$ In words, we penalize the snippet missing a note wherever the melody has a note. In addition, I found it was a good idea to penalize notes that are at most a whole step away from the melody, because these notes tend to create dissonance with the melody. This can be done by adding an error term that sums all the squared values of $S$ that are within two steps of a melody note, but not on a melody note.

With an error term in hand, it's easy to do gradient descent on the labels $L$: $$ L[i] := L[i] - \alpha \cdot \frac{\partial err(gen(L))}{\partial L[i]} $$ This gets us to a local minimum in the error with respect to $L$. We then output the entire $gen(L)$, and superimpose the original melody on top, because $gen(L)$ doesn't usually reproduce the melody perfectly.

The results sound something like this, for Jingle Bells: attempt 1![]() , attempt 2

, attempt 2![]() . In general, there's reasonable use of chords throughout, but some odd dissonances still.

. In general, there's reasonable use of chords throughout, but some odd dissonances still.

And since that got me in a Christmas mood, here's another carol: attempt 1![]() , attempt 2

, attempt 2![]() . It seems that "12 Days of Christmas" is a little harder for our neural net, because it has a more complicated melody.

. It seems that "12 Days of Christmas" is a little harder for our neural net, because it has a more complicated melody.

Inspirations and coincidences

This project was originally built for MIT's Interactive Music Systems class (21M.359), taught by Eran Egozy of Guitar Hero fame. At the time (March 2015), I became interested in applying neural nets to music after seeing Greg Bickerman's paper on using DBNs to improvise jazz melodies. That paper tries to learn melodies - I wanted to learn harmonies as well. This YouTube video on music generation also helped kick this project from "I don't think this is possible" to "Let's try this" territory.

I did the bulk of the engineering for this project in April and May, using the DBN tutorial code in Theano as a starting point. If you'd like to play with the code yourself, it is on GitHub, but be warned - it's quite hacky, though I've tried to clean it up after project deadlines passed. In particular, there is some trouble dealing with 32 vs 64 bit architectures. Since then, there have been several other really cool projects involving music and deep learning. They didn't actually influence this project very much, but I would feel bad not talking about them, and they are quite neat.

The first related project is Daniel Johnson's work on using recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to generate music. RNNs have an advantage over the DBNs that I use, in that RNNs are time-aware. They use the shared weights idea I introduced earlier in the time domain, so each timestamp is handled by a set of neurons with identical weights. To allow information to travel from timestep to timestamp, RNNs have "recursive" connections across time, from one neuron to itself in the future. Though I was aware of recursive networks at the time, I wasn't confident enough in my understanding of neural networks to try to use them. If I have the time, I want to try applying an RNN to my data, because the results in the link above are pretty impressive.

There's also a paper on generating raw audio waveforms using neural nets, by students in Stanford's NLP class. Their YouTube demo summarizes the project rather nicely - they train a neural net to generate techno music, and surprisingly enough, it actually learns to generate a beat really quickly. (According to the YouTube comments, there is evidence of overfitting later in the song.)

Finally, I have to mention Google's DeepDream open source repo, which looks startlingly like my harmonization code, except for images instead of audio. (I even named my project accordingly.) Both my project and DeepDream use a "prior sampling" algorithm that does gradient descent over the input parameters. I will swear that I came up with the idea independently of Google, though I suppose I shouldn't be expecting any credit.

Thanks to kitchWWW for his clone of MIDIjs, because sometime between 2015 and 2018, MIDI support on the web got even worse.